Preah Poan

The name of this cruciform gallery – ‘the Thousand Buddhas’ – dates from the Middle Period, when the prestige of Angkor Wat spread across Buddhist Asia. Over the course of time the faithful erected here a great number of statues of the Buddha in stone, wood or metal, hence the gallery’s name. Some of the statues still remain while others are exhibited or kept in conservation storehouses. Others have, for diverse reasons, been lost forever. Together, these Buddhist statues testify to an artistic school unique to the temple of Angkor Vat.

The majority of Angkor Wat’s 41 inscriptions dating from the Middle Period are found here, on the pillars of Preah Poan. Largely in Khmer, sometimes including Pali phrases, they date from the 16th to 18th centuries and record pious works performed at Preah Pisnulok by pilgrims, including members of the royal family. The authors inscribe their “vows of truth” and declare their “pure faith” in the religion of the Buddha. These stone inscriptions make an invaluable contribution to our understanding of the ideology of Theravada Buddhism as it became Cambodia’s principal and official religion. Inscriptions in other languages, such as Burmese and Japanese, further demonstrate the cross-cultural attraction the temple has long exerted.

Bakan

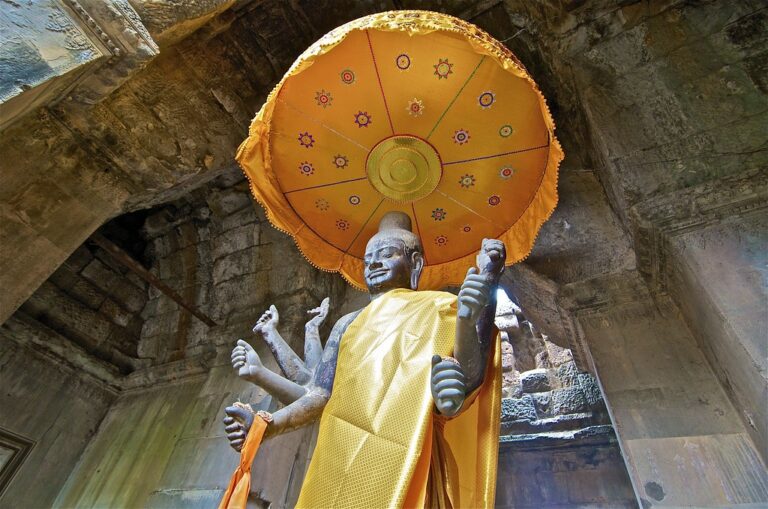

Originally the principal sanctuary of Angkor Wat’s uppermost terrace was open to the four cardinal points, and probably sheltered a statue of Vishnu, the supreme god of the temple. Later, when Angkor Wat became a center of Buddhist pilgrimage, the four entranceways into the central sanctuary were filled in with sandstone blocks; each of the newly constituted walls was then sculpted with a deep relief of the standing Buddha. In 1908 archaeologists opened the southern entranceway. In the place of any original Vishnu statue, they found multiple statue and pedestal fragments, as well as a sarcophagus. Further research carried out in the well of the central sanctuary in the 1930s revealed, at a depth of 23 meters, the temple’s original foundation deposits: two circular gold leaves embedded in a laterite block.

A number of inscriptions at Preah Poan and Bakan, along with the artistic style of these Buddha figures, indicate that the enclosure of the central tower and its transformation into a Buddhist sanctuary was a royal work executed in the latter half of the 16th century. This architectural and iconographic transformation translated into space the conceptual transformation of the central Brahmanic sanctuary into a Buddhist stupa. Here the four Buddhas of the past, facing each of the four cardinal points, surround the garbha – the maternal matrix – which encloses Maitreya, the Buddha of the future. The Bakan illustrates in a most spectacular manner the evolution of Angkor Wat over time: as the ancient Vishnuite temple became a sacred Theravadin Buddhist site, Angkor Wat undoubtedly played a primary role in the conversion of Cambodia into a Theravadin nation.

Angkor Wat Today

Angkor Wat has always figured on Cambodia’s national flag. The temple symbolizes the soul of the Khmer people, and the lasting grandeur of their past. Since December 1992, Angkor Wat and other Angkorian monuments have been classed as UNESCO “World Heritage”. This is a great honor for Cambodia, and a major national obligation. We are responsible for Angkor’s preservation not only before history and in respect of our ancestors, but also, today, before the entire international community.